Carbon and the Global Carbon Cycle

Carbon is a ubiquitous element on Earth. Most of the Earth’s carbon is stored in rocks, but this carbon is essentially inert on the 100’s to 1000’s year timescales of interest to humans. The rest of the carbon is stored as CO2 (carbon dioxide) in the atmosphere (2%), as biomass in land plants and soils (5%), as fossil fuels in a variety of geologic reservoirs (8%) and as a collection of ions in the ocean (85%). These are the “active” reservoirs of carbon of interest in this website.

How are the Global Carbon Cycle and Climate Change connected?

The Earth is warmed by the Sun. This warmth is returned from Earth to the atmosphere in the form of heat radiation. Many gases in the atmosphere, including CO2, absorb the Earth’s heat energy and radiate in all directions. The energy radiated downward warms the surface and lower atmosphere. Adding more CO2 to the atmosphere means more heat radiation is captured by the atmosphere and radiated back to Earth. The accumulation of CO2 in the atmosphere is the dominant driver of climate change (also known as global warming) that is now occurring, with increasingly dramatic impacts on human and natural systems.

This website addresses the emissions, cycling, and critical sinks for CO2 in the ocean and terrestrial biosphere at the global scale. Methane (CH4), another very important greenhouse gas, is not addressed here.

Humans add CO2 to the Atmosphere, Nature removes about half of it.

From 2014-2023, humans added 10.8 billion tons of carbon as CO2 to the atmosphere each year (1 Gigaton = 1 GtC = 1 Petagram of carbon = 1 PgC = 10^15 grams of carbon). This was primarily due to burning fossil fuels (~9.7 PgC/yr) and also from land use change (~1.1 PgC/yr). The ocean took up 27% of this carbon (~2.9 PgC/yr), and the land biosphere absorbed 30% (~3.2 PgC/yr), while 5% of emissions remain unaccounted for (Friedlingstein et al. 2024). Thus, over this recent decade, only ~48% of the carbon emitted by humans remained in the atmosphere to cause climate warming. Though uncertainties remain, it is clear that natural processes are significantly damping the rate of carbon accumulation in the atmosphere (Crisp et al. 2022). Future climate warming depends on both CO2 sources from human emissions and land use, as well as these enormous CO2 sinks in the ocean and the terrestrial biosphere.

Carbon Cycle

The Basics

Carbon is transferred between CO2 and living or dead organic material by the very basic photosynthesis / respiration reaction (shown here in simplified form).

CO2+H2O+energy <=> CH2O + O2

When this reaction proceeds to the right, it is the fixation of carbon to organic matter by plants via photosynthesis; and when it proceeds to the left, it is respiration or combustion of that organic matter. Fossil fuels are the remnants of dead organic matter that lived millions of years ago.

The Global Carbon Cycle

The carbon cycle is a complex system of biological, chemical and physical processes. A schematic from the 2024 Global Carbon Budget (Friedlingstein et al. 2024) report is shown here. The schematic shows the major reservoirs of carbon in gigatons of carbon, GtC and the major fluxes in GtC/yr for 2014-2023.

These flux estimates are updated annually by the Global Carbon Project (Friedlingstein et al. 2024) and the state of carbon cycle science is also reviewed in each IPCC report (Canadell, Monteiro et. al 2021).

Schematic representation of the overall perturbation of the global carbon cycle caused by anthropogenic activities averaged globally for the decade 2014–2023. The anthropogenic perturbation occurs on top of an active carbon cycle, with fluxes and stocks represented in the background and taken from Canadell et al. (2021). Figure 2 of Friedlingstein et al. 2024.

References

Atmosphere

In 1958, Charles D. Keeling began taking measurements of atmospheric CO2 at Mauna Loa, Hawaii. One can see both the seasonal cycle, dominated by the annual cycle of photosynthesis and respiration in the terrestrial biosphere of the Northern Hemisphere, as well as the clear upward trend. Learn more about Keeling's data from this short video from the American Museum of Natural History .

These data are now part of a global network that monitors atmospheric CO2. All observations show a steadily increasing trend. You can find the data and other information from the National Atmospheric and Oceanic Administration Global Monitoring Lab (NOAA GML). NOAA has also produced this great visualization of current observations across latitudes and puts them in context with historical CO2 records that stretch back to the ice ages.

As explained below, CO2 is accumulating in the atmosphere because of human activities, primarily the burning of fossil fuels and the clearing of forests for cultivation. You will also learn about how natural processes on land and in the ocean are significantly modulating the rate of CO2 growth in the atmosphere.

References

Fossil Fuels

The Basics

Burning fossil fuels puts carbon into the atmosphere. Other smaller sources include industrial processes such as cement manufacture and natural gas flaring. Fossil fuels provide most of the energy that supports human transportation, electricity production, heating and cooling of buildings, and industrial activity. Oil used to be the dominant fossil fuel, but since the early 2000s, coal has become dominant and the share from natural gas is also steadily growing.

In the 1990’s, human fossil fuel use emitted 6.4 Petagrams of carbon per year (PgC/yr), while in 2014-2023, 9.7 PgC/yr. Over 2000-2009, emissions increased by 2.8% per year, substantially faster than the growth rate of 1.0% per year in the 1990’s. This dramatic increase was primarily due to growing emissions from developing countries. From 2014-2023, the rate of emissions growth was 0.6% per year. This reduced growth rate is a positive sign with respect to climate, but still carbon emissions are growing every year. Meeting international goals of limiting climate warming to less that 2 degrees C will require us to rapidly reverse this long-standing pattern of ever-increasing emissions. To safeguard the climate, emissions must be reduced - not increased - each and every year.

Since 2000, emissions have grown rapidly in developing countries, particularly China. This has been due in some part to increasing energy use and consumption domestically, but also has a significant component due to the production of goods that have been exported to developed countries for consumption. Emissions from all countries, as well as these production / consumption flows, are estimated annually by the Global Carbon Project .

The Future of Fossil Fuels

The future of anthropogenic fossil fuel use depends on human decisions about energy use at scales from local to global. If we do not change our historical pattern of fossil fuel dependency, emissions will continue to increase. But this is not the only option - we already have the knowledge and technologies needed to change these patterns so that we can rapidly cut emissions. This will require transforming energy systems to be dominated by renewables, changing food systems to be less carbon intensive and less wasteful, and modifying transportation patterns and infrastructure to use far less energy. If we do these things, emissions will come down, which in turn will reduce the damages and suffering that we and our children will experience due to climate change. To reform our fossil fuel-based economies will entail difficult political and social decisions from the local to the global scale. But this is not an impossible problem if everyone contributes to our low carbon future. Thank you for doing all you can!

Reducing emissions of CO2 and other greenhouse gases is the focus of the activities of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. A major upcoming step is the first global stocktake of the 2015 Paris Agreement that will occur at COP28 in late 2023.

References

Ocean Uptake

The Basics

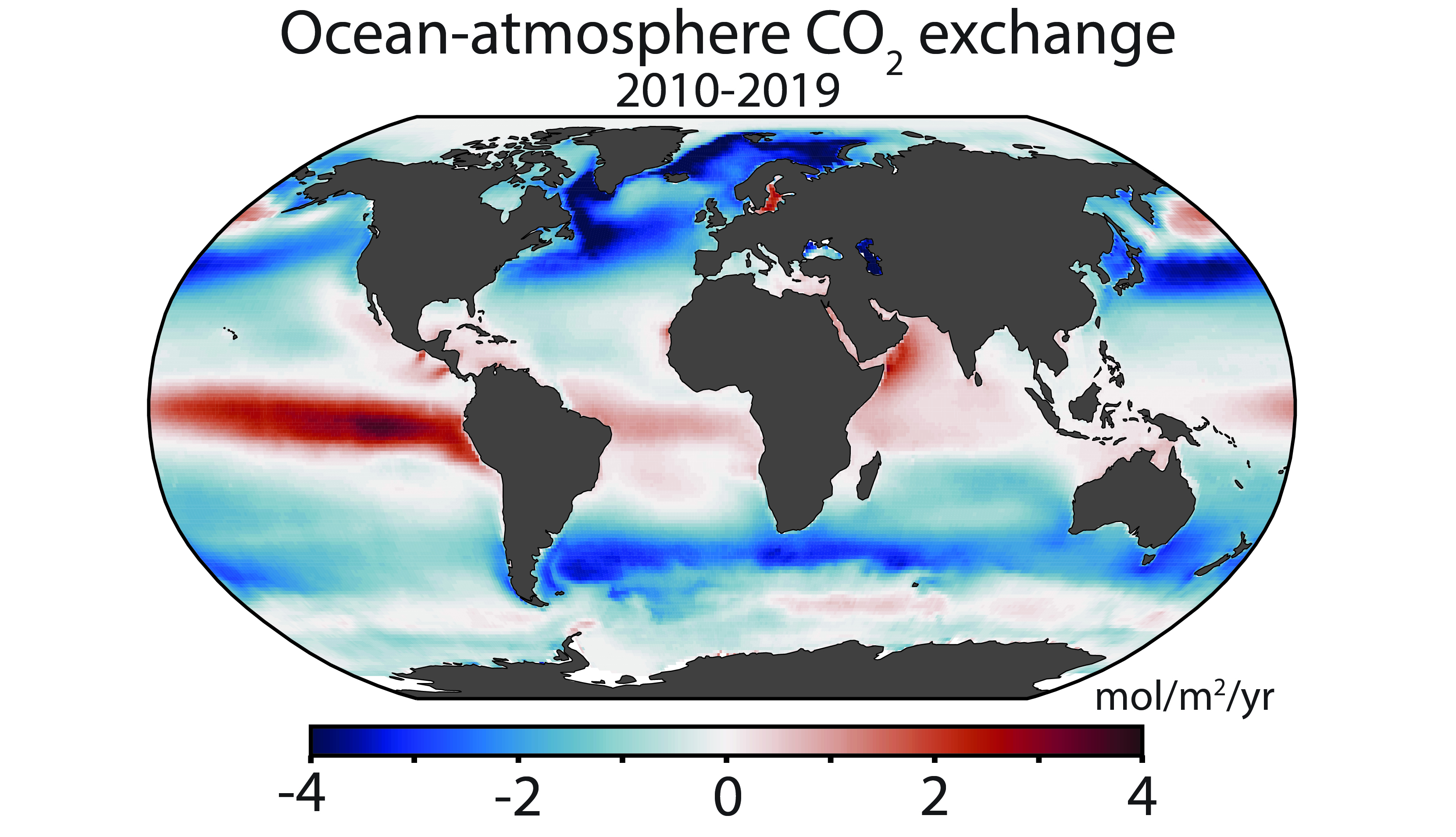

CO2 dissolves in seawater, and then reacts with the water so that it dissociates into several ions. This disassociation means that the oceans can hold a lot of carbon – 85% of the active reservoir on Earth. Cold seawater can hold more CO2 than warm water, so waters that are cooling (i.e. poleward-moving currents such as the Gulf Stream) tend to take up carbon, and waters that are upwelling and warming (i.e. coastal zones and the tropics) tend to emit carbon. This contributes to the pattern of the global sea-to-air CO2 flux, as shown in this global map.

Annual mean air-sea CO2 flux, 2010-2019, based on observations (McKinley et al. 2023). Positive is from ocean to atmosphere, negative from atmosphere to ocean.

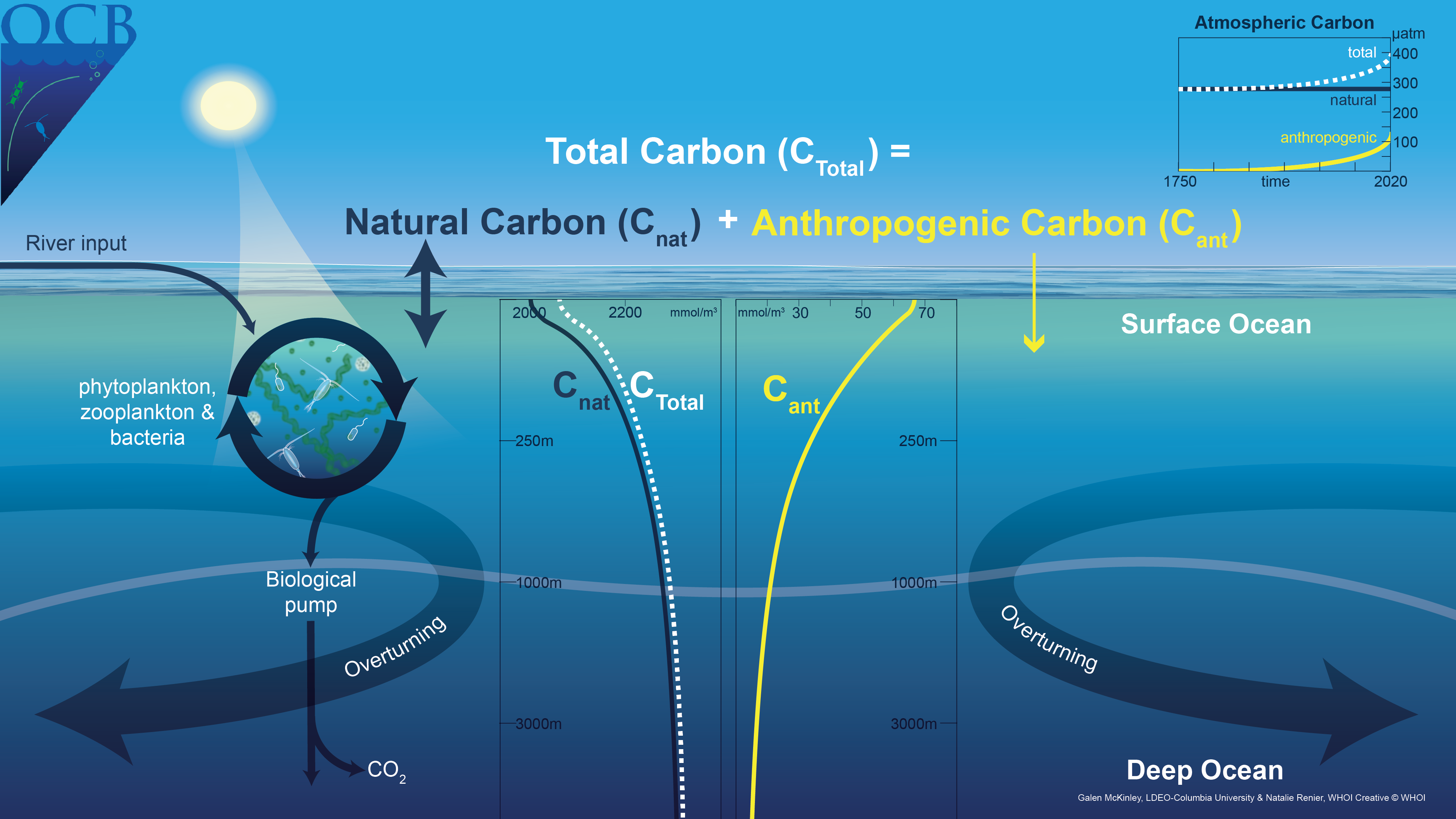

The ocean is also teeming with plant life that photosynthesizes in the presence of nutrients and sunlight and makes organic matter out of the carbon in seawater. Though much of the carbon removed from seawater biologically is quickly recycled back to carbon by the surface ocean food web, a small portion (less than 1%) of the waste matter sinks down to depth and enriches the abyss with carbon (left panel below). This process moves carbon from the surface ocean to the deep ocean and stores carbon away from the atmospheric reservoir. Regionally, the high latitude oceans are highly productive, and this is another reason that high latitude oceans absorb large quantities of CO2 (see map above).

The ocean carbon cycle, surface to depth. On the left is the natural carbon cycle that includes biological production, ocean circulation and air-sea exchange. On the right is the anthropogenic carbon cycle that includes invasion of carbon into the surface ocean due to the growing atmospheric pCO2 (inset on top right), and the ocean circulation that mixes anthropogenic carbon to depth. The total carbon cycle, is the sum of the natural and anthropogenic cycles. At center are the observed global-mean profiles of natural, anthropogenic and total carbon in the ocean. The air-sea flux presented in the global map above is for the total carbon cycle. Figure by Galen McKinley and Natalie Renier, with support from the OCB program.

As humans increase the atmospheric CO2 concentration, more carbon is driven into the oceans (right panel of figure above). The basic physics in operation is Henry's Law, here operating at the global scale. This excess load of carbon is almost all in the surface 1km and only slowly penetrates to depth (Gruber et al. 2019). This is because the ocean takes about 1000 years to fully mix.

If not for the ocean, the atmospheric concentration of CO2 would be about 90ppm higher than at present (equivalent to 185 PgC). Of all fossil fuel emissions to the atmosphere (490 PgC) since 1850, the ocean has cumulatively mitigated 38% and the rest has remained in the atmosphere (Friedlingstein et al. 2024). Here is an animation of the changing balance of carbon sources and sinks since 1850.

Animation of the cumulative global budget for anthropogenic carbon, 1850-2023 (data compiled by Friedlingstein et al. 2024). Animation made by Marit Jentoft-Nilsen, NASA.

The Future of Ocean Carbon Uptake

The ocean will eventually take up about 85% of anthropogenic CO2, but because the ocean takes about 1000 years to mix, this process will take many hundreds to thousands of years.

In this century, the ocean carbon sink will grow in rough proportion to carbon emissions because atmospheric CO2 is the primary driver of the sink (McKinley et al. 2020). In the coming decades, as emissions go up, the absolute magnitude of the ocean carbon sink will increase in magnitude, and as emissions go down, the ocean sink will become smaller. However, the percentage of human emissions that the ocean will be able to absorb will be larger with greater emission reductions (McKinley et al. 2023). There are other processes likely to slow the sink if emission are not cut significantly: the chemical capacity for carbon will increasingly be depleted, and warming and ice melt may slow down the large-scale overturning circulation. Impacts on carbon uptake due to future change in ocean biology is a major uncertainty. Current predictions suggest regional changes in biological productivity, but a small net effect on global carbon uptake; however, these predictions are very uncertain (Seigel et al. 2023).

Scientists can learn how the ocean carbon sink changes by studying its recent variability (Gruber et al. 2023). In the Southern Ocean, observations suggest the sink weakened over the 1990s, and then strengthened again. Though many have tried, these changes have yet to be fully explained. Increasing the quantity of surface ocean carbon observations will likely be critical to solving this puzzle (Bakker et al. 2016, Gloege et al. 2021, Heimdal et al. 2023).

Research and enhanced observations will improve our knowledge of how the ocean carbon sink operates, and let us track this critical carbon reservoir as it evolves with climate change. In the US, the Ocean Carbon and Biogeochemistry (OCB) program coordinates research on ocean carbon uptake. See a short film here that summarizes their portfolio. The International Ocean Carbon Coordinating Project (IOCCP) plays a critical role in international efforts.

The “Other CO2 Problem” = Ocean Acidification

There are additional consequences to the ocean’s uptake of carbon. CO2 dissolved in seawater and forms carbonic acid, and so adding more CO2 to the water makes the ocean more acidic. From preindustrial times to present the pH of the ocean has declined 0.1 pH units, from 8.21 to 8.10, and it is likely to decline by another 0.3-0.4 pH units by the 2100, assuming atmospheric pCO2 is about 800 ppmv by that time. Acidification will damage coral reefs and likely place significant stress on species important to ocean food chain, particularly in the Southern Ocean. Scientists are working hard to better-understand the impacts on organisms and the integrated effects on ocean ecosystems.

To learn more about ocean acidification, check out resources from Natural Resources Defense Council , NOAA and the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.

References

Land Use

The Basics

New agricultural land is typically created by cutting down forests. When trees are cut down and burned or left to decompose, carbon goes into the atmosphere. In the present day, deforestation and the resulting net carbon source to the atmosphere is primarily occurring in the tropics. However, in the last 200 years, forest clearing for agriculture in the middle latitudes of the Northern Hemisphere was also a substantial source of carbon to the atmosphere. Since the mid-1900’s, much of the less-productive agricultural land in the US and Europe has been allowed to regrow as forests – making for uptake of carbon from the atmosphere through carbon accumulation in woody biomass and soils. Uncertainty in estimates of the land use source are large in part because estimates of deforestation and other land use changes are, themselves, quite uncertain. In addition, the amount of carbon stored in the forests is not well-quantified. (Crisp et al. 2022)

Agriculture, Forestry and other Land Use (AFOLU) led to 13% of CO2 emissions over 2007-2016 (IPCC 2022), and 10% for 2014-2023 (Friedlingstein et al. 2024). AFOLU is also a major source for non-CO2 greenhouse gases (CH4, N20).

The Future of Land Use

The future of land use on Earth depends on many factors. Human decisions at scales from local to global will change Earth's forests, agriculture, soils, wildlands and urban footprints. If people decide to grow large quantities of biofuels to replace fossil fuels, this will have major land use implications. In a 2022 special IPCC report, these and other factors were considered to develop a range of future scenarios.

What is the difference between Land Use and Land Uptake?

These terms are separated to clarify the direct impact of humans in clearing of forests and other lands, and subsequent regrowth (Land Use), from the natural system’s response to anthropogenic addition of carbon to the atmosphere and climate warming (Land Uptake). In many studies, however, it is impractical to distinguish between these two terms. Often some of what should be formally classified as Land Use (such as afforestation in the mid-latitudes) gets included in Land Uptake.

References

Land Uptake

The Basics

The land (or terrestrial) biosphere takes up and releases enormous amounts of carbon each year as it cycles through periods of growth and dormancy. Growth leads to the accumulation of carbon in leaves and stalks, woody parts, roots, and in soils. Decay of dead matter, primarily on the ground and in soils, returns carbon to the atmosphere. This cycling can be seen in the red trace of seasonality in observed atmospheric CO2, shown on the Atmosphere tab.

Land plants are sensitive to short-term changes in climate that make for variable quality of growing seasons, and are vulnerable to extreme events such as fire, drought and flooding. These effects make for substantial year-to-year variability in the magnitude of the carbon uptake by the terrestrial biosphere. This can be seen in the historical record shown in bright green in the applet.

Why is the Land Biosphere Absorbing Atmospheric CO2?

The land biosphere has taken up one-third of anthropogenic carbon emissions in recent decades. This occurs due to the physiological or metabolic responses by plants to the increasing CO2 concentration in the atmosphere, climate warming, and increasing nitrogen availability. (1) The “CO2 fertilization effect” can be explained as follows: Plants need CO2 as a building block in photosynthesis, so having more CO2 in the air provides more of this resource; and CO2 can be acquired more quickly through stomata which reduces water loss. (2) Warming stimulates longer growing seasons, particularly at higher latitudes. (3) Human activities have dramatically sped up global nitrogen cycling, which makes nitrogen more available to plants. (4) Previously disturbed forests are recovering from prior deforestation, especially in the Northern hemisphere. The relative importance of each of these factors remains in debate, and there may be important synergies between them. (Denning 2022)

Quantifying the uptake of carbon occurring in land biosphere is challenging. Heterogeneity across and within forests, prairies, agriculture lands, and in the soil makes extrapolation from small-scale studies difficult. There are poorly-quantified horizontal transfers occurring in groundwater, in inland waters and to the coastal ocean (Reginer et al. 2022). Global scale budget efforts are confounded by insufficient data and uncertainty in the atmospheric transport. In recent years, new satellite-based CO2 observations are helping to constrain regional and global CO2 fluxes, particularly those from the land biosphere (Crisp et al. 2022).

The Future of Land Uptake

In the applet, you can see that the IPCC range for future Land Uptake is large. Imprecise predictions are directly related to our uncertainty with respect to modern-day processes. For example, the “CO2 fertilization effect” of enhanced growth with more CO2 has been shown by some studies to be a temporary effect, saturating in natural systems after a few years. Uncertainty in how long “CO2 fertilization" can be sustained drives much of the range in IPCC predictions. There is less known about nitrogen fertilization and its possible future role. (Denning 2022)

It is possible that the land biosphere could become a natural source of carbon to the atmosphere, as seen in the applet. Persistent drought will contribute to increased forest fires that release carbon. Carbon release is already happening as wildfire extent and damage (US Forest Service via US EPA) increases in the western US. In addition, much organic carbon is stored in permafrost and soils. Warming will lead to thawing and increased microbial activity that will degrade this material and release CO2 to the atmosphere. How much carbon will be released? How much warming must happen before large carbon fluxes occur? These are pressing research questions.

Better understanding the many facets of the land carbon cycle requires lots of data collection and research. In the US, the North American Carbon Program coordinates land carbon research activities.